Codin' Dirty

Carson Gross

“Writing clean code is what you must do in order to call yourself a professional. There is no reasonable excuse for doing anything less than your best.” Clean Code

In this essay I want to talk about how I write code. I am going to call my approach “codin’ dirty” because I often go against the recommendations of Clean Code, a popular approach to writing code.

Now, I don’t really consider my code all that dirty: it’s a little gronky in places but for the most part I’m happy with it and find it easy enough to maintain with reasonable levels of quality.

I’m also not trying to convince you to code dirty with this essay. Rather, I want to show that it is possible to write reasonably successful software this way and, I hope, offer some balance around software methodology discussions.

I’ve been programming for a while now and I have seen a bunch of different approaches to building software work. Some people love Object-Oriented Programming (I like it), other very smart people hate it. Some folks love the expressiveness of dynamic languages, other people hate it. Some people ship successfully while strictly following Test Driven Development, others slap a few end-to-end tests on at the end of the project, and many people end up somewhere between these extremes.

I’ve seen projects using all of these different approaches ship and maintain successful software.

So, again, my goal here is not to convince you that my way of coding is the only way, but rather to show you (particularly younger developers, who are prone to being intimidated by terms like “Clean Code”) that you can have a successful programming career using a lot of different approaches, and that mine is one of them.

TLDR

Three “dirty” coding practices I’m going to discuss in this essay are:

- (Some) big functions are good, actually

- Prefer integration tests to unit tests

- Keep your class/interface/concept count down

If you want to skip the rest of the essay, that’s the takeaway.

I Like Big Functions

I think that large functions are fine. In fact, I think that some big functions are usually a good thing in a codebase.

This is in contrast with Clean Code, which says:

“The first rule of functions is that they should be small. The second rule of functions is that they should be smaller than that.” Clean Code

Now, it always depends on the type of work that I’m doing, of course, but I usually tend to organize my functions into the following:

- A few large “crux” functions, the real meat of the module. I set no bound on the Lines of Code (LOC) of these functions, although I start to feel a little bad when they get larger than maybe 200-300 LOC.

- A fair number of “support” functions, which tend to be in the 10-20 LOC range

- A fair number of “utility” functions, which tend to be in the 5-10 LOC range

As an example of a “crux” function, consider the issueAjaxRequest()

in htmx. This function is nearly 400 lines long!

Definitely not clean!

However, in this function there is a lot of context to keep around, and it lays out a series of specific steps that must proceed in a fairly linear manner. There isn’t any reuse to be found by splitting it up into other functions and I think it would hurt the clarity (and also importantly for me, the debuggability) of the function if I did so.

Important Things Should Be Big

A big reason I like big functions is that I think that in software, all other things being equal, important things should be big, whereas unimportant things should be little.

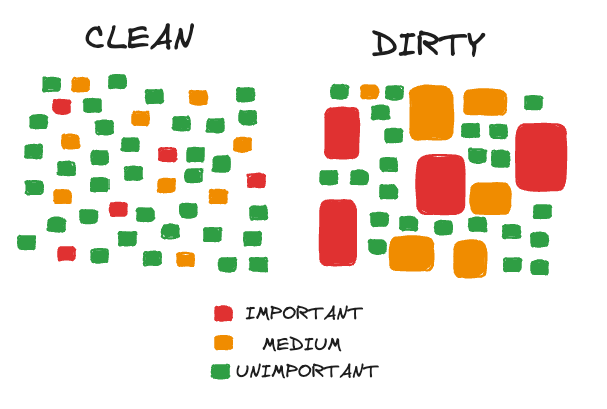

Consider a visual representation of “Clean” code versus “Dirty” code:

When you split your functions into many equally sized, small implementations you end up smearing the important parts of your implementation around your module, even if they are expressed perfectly well in a larger function.

Everything ends up looking the same: a function signature definition, followed by an if statement or a for loop, maybe a function call or two, and a return.

If you allow your important “crux” functions to be larger it is easier to pick them out from the sea of functions, they are obviously important: just look at them, they are big!

There are also fewer functions in general in all categories, since much of the code has been merged into larger functions. Fewer lines of code are dedicated to particular type signatures (which can change over time) and it easier to keep the important and maybe even the medium-important function names and signatures in your head. You also tend to have fewer LOC overall when you do this.

I prefer coming into a new “dirty” code module: I will be able to understand it more quickly and will remember the important parts more easily.

Empirical Evidence

What about the empirical (dread word in software!) evidence for the ideal function size?

In Chapter 7, Section 4 of Code Complete, Steve McConnell lays out some evidence for and against longer functions. The results are mixed, but many of the studies he cites show better errors-per-line metrics for larger, rather than smaller, functions.

There are newer studies as well that argue for smaller functions (<24 LOC) but that focus on what they call “change-proneness”. When it comes to bugs, they say:

Correlations between SLOC and bug-proneness (i.e., #BuggyCommits) are significantly lower than the four change-proneness indicators.

And, of course, longer functions have more code in them, so the correlation of bug-proneness per line of code will be even lower.

Real World Examples

How about some examples from real world, complex and successful software?

Consider the sqlite3CodeRhsOfIn()

function in SQLite, a popular open source database. It looks to be > 200LOC, and a walk around the SQLite

codebase will furnish many other examples of large functions. SQLite is noted for being extremely high quality and

very well maintained.

Or consider the ChromeContentRendererClient::RenderFrameCreated()

function in the Google Chrome Web Browser. Also looks to be over 200 LOC. Again, poking around the codebase

will give you plenty of other long functions to look at. Chrome is solving one of the hardest problems in software:

being a good general purpose hypermedia client. And yet their code doesn’t look very “clean” to me.

Next, consider the kvstoreScan()

function in Redis. Smaller, on the order of 40LOC, but still far larger than Clean Code would

suggest. A quick scan through the Redis codebase will furnish many other “dirty” examples.

These are all C-based projects, so maybe the rule of small functions only applies to object-oriented languages, like Java?

OK, take a look at the update()

function in the CompilerAction class of IntelliJ, which is roughly 90LOC. Again,

poking around their codebase will reveal many other large functions well over 50LOC.

SQLite, Chrome, Redis & IntelliJ…

These are important, complicated, successful & well maintained pieces of software, and yet we can find large functions in all of them.

Now, I don’t want to imply that any of the engineers on these projects agree with this essay in any way, but I think that we have some fairly good evidence that longer functions are OK in software projects. It seems safe to say that breaking up functions just to keep them small is not necessary. Of course you can consider doing so for other reasons such as code reuse, but being small just for small’s sake seems unnecessary.

I Prefer Integration Tests to Unit Tests

I am a huge fan of testing and highly recommend testing software as a key component of building maintainable systems.

htmx itself is only possible because we have a good test suite that helps us ensure that the library stays stable as we work on it.

If you take a look at the test suite one thing you might notice is the relative lack of Unit Tests. We have very few test that directly call functions on the htmx object. Instead, the tests are mostly Integration Tests: they set up a particular DOM configuration with some htmx attributes and then, for example, click a button and verify some things about the state of the DOM afterward.

This is in contrast with Clean Code’s recommendation of extensive unit testing, coupled with Test-First Development:

First Law You may not write production code until you have written a failing unit test. Second Law You may not write more of a unit test than is sufficient to fail, and not compiling is failing. Third Law You may not write more production code than is sufficient to pass the currently failing test.

I generally avoid doing this sort of thing, especially early on in projects. Early on you often have no idea what the right abstractions for your domain are, and you need to try a few different approaches to figure out what you are doing. If you adopt the test first approach you end up with a bunch of tests that are going to break as you explore the problem space, trying to find the right abstractions.

Further, unit testing encourages the exhaustive testing of every single function you write, so you often end up having more tests that are tied to a particular implementation of things, rather than the high level API or conceptual ideas of the module of code.

Of course, you can and should refactor your tests as you change things, but the reality is that a large and growing test suite takes on its own mass and momentum in a project, especially as other engineers join, making changes more and more difficult as they are added. You end up creating things like test helpers, mocks, etc. for your testing code.

All that code and complexity tends over time to lock you in to a particular implementation.

Dirty Testing

My preferred approach in many projects is to do some unit testing, but not a ton, early on in the project and wait until the core APIs and concepts of a module have crystallized.

At that point I then test the API exhaustively with integrations tests.

In my experience, these integration tests are much more useful than unit tests, because they remain stable and useful even as you change the implementation around. They aren’t as tied to the current codebase, but rather express higher level invariants that survive refactors much more readily.

I have also found that once you have a few higher-level integration tests, you can then do Test-Driven development, but at the higher level: you don’t think about units of code, but rather the API you want to achieve, write the tests for that API and then implement it however you see fit.

So, I think you should hold off on committing to a large test suite until later in the project, and that test suite should be done at a higher level than Test-First Development suggests.

Generally, if I can write a higher-level integration test to demonstrate a bug or feature I will try to do so, with the hope that the higher-level test will have a longer shelf life for the project.

I Prefer To Minimize Classes

A final coding strategy that I use is that I generally strive to minimize the number of classes/interfaces/concepts in my projects.

Clean Code does not explicitly say that you should maximize the # of classes in your system, but many recommendations it makes tend to lead to this outcome:

- “Prefer Polymorphism to If/Else or Switch/Case”

- “The first rule of classes is that they should be small. The second rule of classes is that they should be smaller than that.”

- “The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) states that a class or module should have one, and only one, reason to change.”

- “The first thing you might notice is that the program got a lot longer. It went from a little over one page to nearly three pages in length.”

As with functions, I don’t think classes should be particularly small, or that you should prefer polymorphism to a simple (or even a long, janky) if/else statement, or that a given module or class should only have one reason to change.

And I think the last sentence here is a good hint why: you tend to end up with a lot more code which may be of little real benefit to the system.

“God” Objects

You will often hear people criticise the idea of “God objects” and I can of course understand where this criticism comes from: an incoherent class or module with a morass of unrelated functions is obviously a bad thing.

However, I think that fear of “God objects” can tend to lead to an opposite problem: overly-decomposed software.

To balance out this fear, let’s look at one of my favorite software packages, Active Record.

Active Record provides a way for you to map ruby object to a database, it is what is called an Object/Relational Mapping tool.

And it does a great job of that, in my opinion: it makes the easy stuff easy, the medium stuff easy enough, and when push comes to shove you can kick out to raw SQL without much fuss.

(This is a great example of what I call “layering” an API.)

But that’s not all the Active Record objects are good at: they also provide excellent functionality for building HTML in the view layer of Rails. They don’t include HTML specific functionality, but they do offer functionality that is useful on the view side, such as providing an API to retrieve error messages, even at the field level.

When you are writing Ruby on Rails applications you simply pass your Active Record instances out to the view/templates.

Compare this with a more heavily factored implementation, where validation errors are handled as their own “concern”. Now you need to pass (or at least access) two different things in order to properly generate your HTML. It’s not uncommon in the Java community to adopt the DTO pattern and have another set of objects entirely distinct from the ORM layer that is passed out to the view.

I like the Active Record approach. It may not be separating concerns when looked at from a purist perspective, but my concern is often getting data from a database into an HTML document, and Active Record does that job admirably without me needing to deal with a bunch of other objects along the way.

This helps me minimize the total number of objects I need to deal with in the system.

Will some functionality creep into a model that is maybe a bit “view” flavored?

Sure, but that’s not the end of the world, and it reduces the number of layers and concepts I have to deal with. Having one class that handles retrieving data from the database, holding domain logic and serves as a vessel for presenting information to the view layer simplifies things tremendously for me.

Conclusion

I’ve given three examples of my codin’ dirty approach:

- I think (some) big functions are good, actually

- I prefer integration tests to unit tests

- I like to keep my class/interface/concept count down

I’m presenting this, again, not to convince you to code the way I code, or to suggest that the way I code is “optimal” in any way.

Rather it is to give you, and especially you younger developers out there, a sense that you don’t have to write code the way that many thought leaders suggest in order to have a successful software career.

You shouldn’t be intimidated if someone calls your code “dirty”: lots of very successful software has been written that way and, if you focus on the core ideas of software engineering, you will likely be successful in spite of how “dirty” it is, and maybe even because of it!