You Can't Build Interactive Web Apps Except as Single Page Applications... And Other Myths

Tony AlaribeAn Ode to Browser Advancements.

I often encounter discussions on Reddit and YCombinator where newer developers seek tech stack advice. Inevitably, someone claims it’s impossible to build a high-quality application without using a single-page application (SPA) framework like React or AngularJS. This strikes me as odd because, even before the SPA revolution, many popular multi-page web applications offered excellent user experiences.

Two years ago, I set out to build an observability platform and chose to experiment with a multi-page application (MPA) approach using HTMX. I wondered: Would a server-rendered MPA be inadequate for a data-heavy application, considering that most observability platforms are built on ReactJS?

What I discovered is that you can create outstanding server-rendered applications if you pay attention to certain details.

Here are some common MPA myths and what I’ve learned about them.

Myth 1: MPA Page Transitions are slow because JavaScript and CSS are downloaded on every page navigation

The perception that MPA page transitions are slow is widespread—and not entirely unfounded—since this is the default behavior of browsers. However, browsers have made significant improvements over the past decade to mitigate this issue.

To illustrate, in the video below, a full page reload with the cache disabled takes 2.90 seconds until the DOMContentLoaded event fires. I recorded this at a café with poor Wi-Fi, but let’s use this as a reference point. Keep that number in mind.

It is common to reduce load times in MPAs using libraries such as PJAX, Turbolinks, and even HTMX Boost. These libraries hijack the page reload using Javascript and swap out only the HTML body element between transitions. That way, most of the page’s head section assets don’t need to be reloaded or re-downloaded.

But there’s a lesser known way of reducing how much assets are re-downloaded or evaluated during page transitions.

Client-side Caching via Service workers

Frontend developers who have built Progressive Web Applications (PWA) with SPA frameworks might know about service workers.

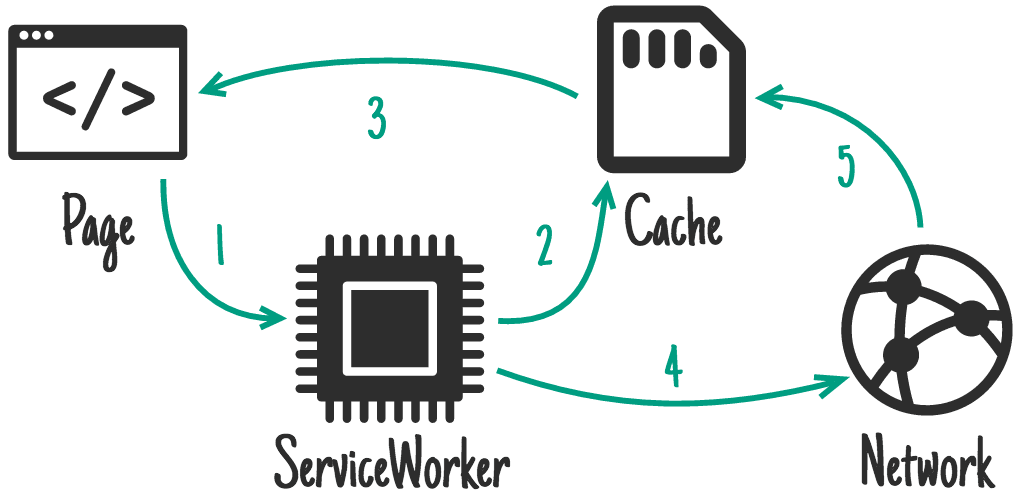

For those of us who are not frontend or PWA developers, service workers are a built-in feature of browsers. They let you write Javascript code that sits between your users and the network, intercepting requests and deciding how the browser handles them.

Due to its association with the PWA trend, service workers are only ordinary among SPA developers, and developers need to realize that this technology can also be used for regular Multi-Page Applications.

In the video demonstration, we enable a service worker to cache and refresh the current page. You’ll notice that there’s no flicker when clicking the link to reload the page, resulting in a smoother user experience.

Moreover, instead of transmitting over 2 MB of static assets as before, the browser now only fetches 84 KB of HTML

content—the actual page data. This optimization reduces the DOMContentLoaded event time from 2.9 seconds to under 500

milliseconds. Impressively, this improvement is achieved without using HTMX Boost, PJAX, or Turbolinks.

How to Implement Service workers in Your Multi-Page Application

You might be wondering how to replicate these performance gains in your own MPA. Here’s a simple guide:

- Create a

sw.jsFile: This is your service worker script that will manage caching and network requests. - List Files to Cache: Within the service worker, specify all the assets (HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images) that should be cached.

- Define Caching Strategies: Indicate how each type of asset should be cached—for example, whether they should be cached permanently or refreshed periodically.

By implementing a service worker, you effectively tell the browser how to handle network requests and caching, leading to faster load times and a more seamless user experience.

Use Workbox to generate service workers

While it’s possible to write service workers by hand—and there are excellent resources like this MDN article to help you—I prefer using Google’s Workbox library to automate the process.

Steps to Use Workbox:

-

Install Workbox: Install Workbox via npm or your preferred package manager:

npm install workbox-cli --global -

Generate a Workbox Configuration file: Run the following command to create a configuration file:

workbox wizard -

Configure Asset Handling: In the generated

workbox-config.jsfile, define how different assets should be cached. Use theurlPatternproperty—a regular expression—to match specific HTTP requests. For each matching request, specify a caching strategy, such asCacheFirstorNetworkFirst.

-

Build the Service Worker: Run the Workbox build command to generate the

sw.jsfile based on your configuration:workbox generateSW workbox-config.js -

Register the Service Worker in Your Application: Add the following script to your HTML pages to register the service worker:

<script> if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) { window.addEventListener('load', function() { navigator.serviceWorker.register('/sw.js').then(function(registration) { console.log('ServiceWorker registration successful with scope: ', registration.scope); }, function(err) { console.log('ServiceWorker registration failed: ', err); }); }); } </script>

By following these steps, you instruct the browser to serve cached assets whenever possible, drastically reducing load times and improving the overall performance of your multi-page application.

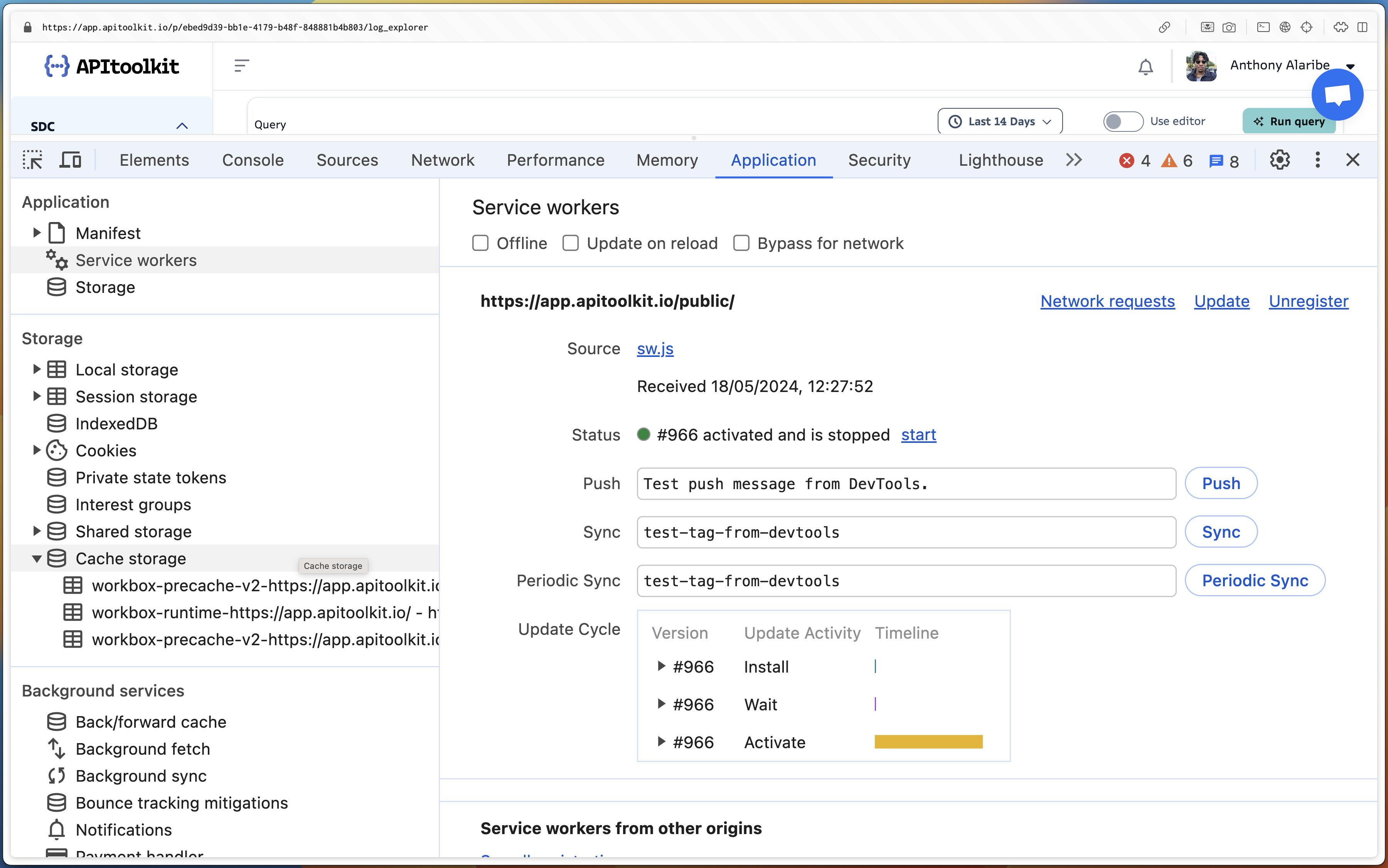

Image showing the registered service worker from the Chrome browser console.

Speculation Rules API: Prerender pages for instant page navigation.

If you have used htmx-preload or instantpage.js, you’re familiar with prerendering and the problem the “Speculation Rules API” aims to solve. The Speculation Rules API is designed to improve performance for future navigations. It has an expressive syntax for specifying which links should be prefetched or prerendered on the current page.

Speculation rules configuration example

The script above is an example of how speculation rules are configured. It is a Javascript object, and without going into detail, you can see that it uses keywords such as “where,” “and,” “not,” etc. to describe what elements should either be prefetched or prerendered.

Example impact of prerendering (Chrome Team)

Myth 2: MPAs can’t operate offline and save updates to retry when there’s network

From the last sections, you know that service workers can cache everything and make our apps operate entirely offline. But what if we want to save offline POST requests and retry them when there is internet?

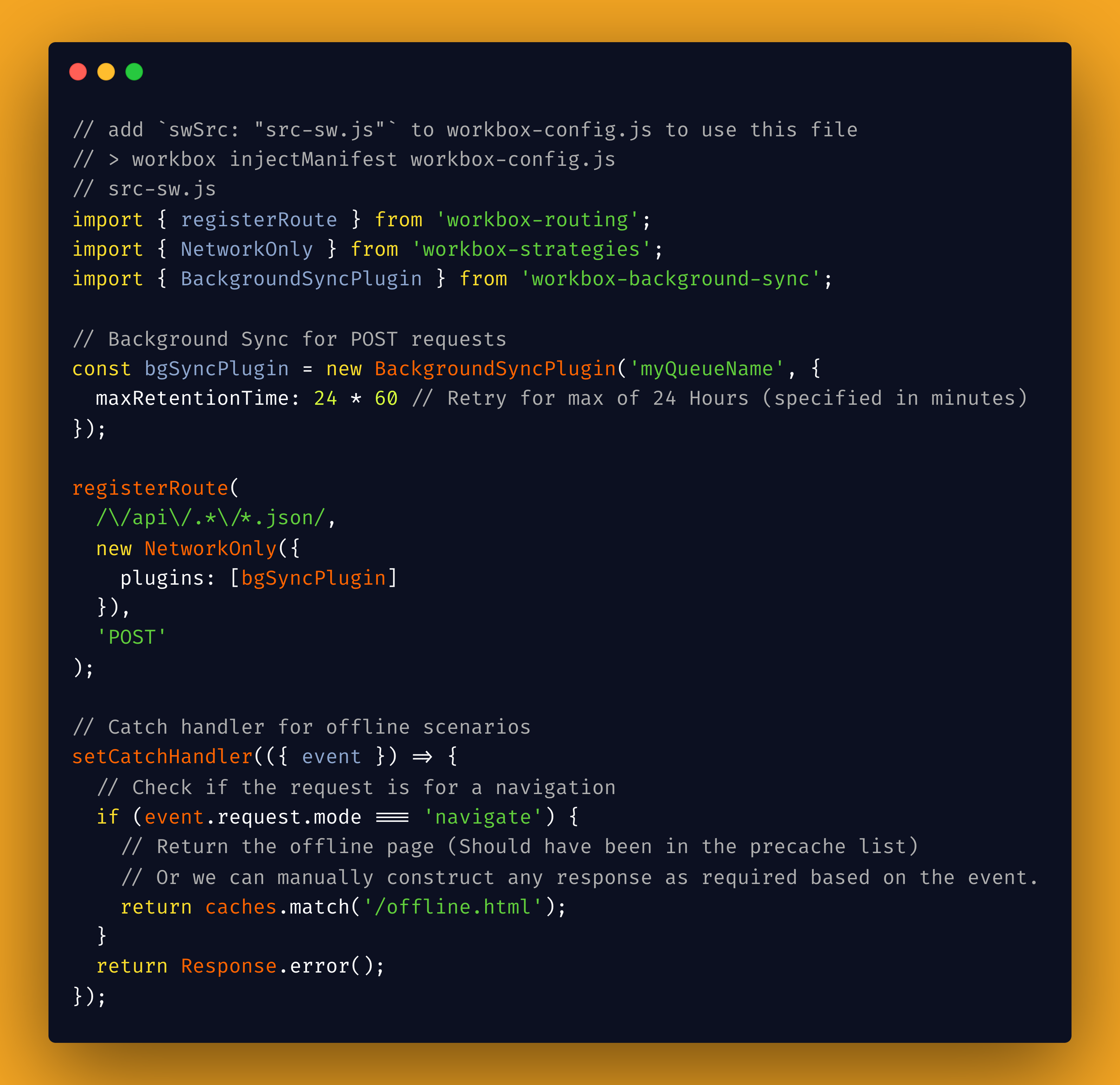

The configuration javascript file above shows how to configure Workbox to support two common offline scenarios. Here, you see background Sync, where we ask the service worker to cache any failed requests due to the internet and retry it for up to 24 hours.

Below, we define an offline catch Handler, triggered when a request is made offline. We can return a template partial with HTML or a JSON response or dynamically build a response based on the request input. The sky is the limit here.

Myth 3: MPAs always flash white during page Transitions

In the service worker videos, we already saw that this will not happen if we configure caching and prerendering. However, this myth was not generally true until 2019. Since 2019, most browsers withhold painting the next screen until all the required assets for the next page are available or a timeout is reached, resulting in no flash of white while transitioning between both pages. This only works when navigating within the same origin/domain.

Paint holding documentation on chrome.com.

Myth 4: Fancy Cross-document page transitions are not possible with MPAs.

The advent of single-page application frameworks made custom transitions between pages more popular. The allure of different navigation styles comes from completely taking control of page navigation from the browsers. In practice, such transitions have mostly been popular within the demos at web dev conference talks.

Cross Document Transitions documentation on chrome.com.

This remains a common argument for single-page applications, especially on Reddit and Hacker News comment sections. However, browsers have been working towards solving this problem natively for the last couple of years. Chrome 126 rolled out cross-document view transitions. This means we can build our MPAs to include those fancy animations and transitions between pages using CSS only or CSS and Javascript.

My favorite bit is that we might be able to create lovely cross-document transitions with CSS only:

You can quickly learn more on the Google Chrome announcement page

This link hosts a multi-page application demo, where you can play around with a rudimentary server-rendered application using the cross-document view transitions API to simulate a stack-based animation.

Myth 5: With htmx or MPAs, every user action must happen on the server.

I’ve heard this a lot when HTMX is discussed. So, there might be some confusion caused by the HTMX positioning. But you don’t have to do everything server-side. Many HTMX and regular MPA users continue to use Javascript, Alpine, or Hyperscript where appropriate.

In situations where robust interactivity is helpful, you can lean into the component islands architecture using WebComponents or any javascript framework (React, Angular, etc.) of your choice. That way, instead of your entire application being an SPA, you can leverage those frameworks specifically for the bits of your application that need that interactivity.

The example above shows a very interactive search component in the APItoolkit. It’s a web component implemented with lit-element, a zero-compile-step library for writing web components. So, the entire web component event fits in a Javascript file.

Myth 6: Operating directly on the DOM is slow. Therefore, it would be best to use React/Virtual DOM.

The speed of direct DOM operations was a major motivation for building ReactJS on and popularizing the virtual DOM technology. While virtual DOM operations can be faster than direct DOM operations, this is only true for applications that perform many complex operations and refresh in milliseconds, where that performance might be noticeable. But most of us are not building such software.

The Svelte team wrote an excellent article titled “Virtual DOM is pure Overhead.” I recommend reading it, as it better explains why Virtual DOM doesn’t matter for most applications.

Myth 7: You still need to write JavaScript for every minor interactivity.

With the advancements in browser tech, you can avoid writing a lot of client-side Javascript in the first place. For

example, a standard action on the web is to show and hide things based on a button click or toggle. These days, you can

show and hide elements with only CSS and HTML, for example, by using an HTML input checkbox to track state. We can style

an HTML label as a button and give it a for="checkboxID“ attribute, so clicking the label toggles the checkbox.

<input id="published" class="hidden peer" type="checkbox"/>

<label for="published" class="btn">toggle content</label>

<div class="hidden peer-checked:block">

Content to be toggled when label/btn is clicked

</div>

We can combine such a checkbox with HTMX intersect to fetch content from an endpoint when the button is clicked.

<input id="published" class="peer" type="checkbox" name="status"/>

<div

class="hidden peer-checked:block"

hx-trigger="intersect once"

hx-get="/log-item"

>Shell/Loading text etc

</div>

All the classes above are vanilla Tailwind CSS classes, but you can also write the CSS by hand. Below is a video of that code being used to hide or reveal log items in the log explorer.

Final Myth: Without a “Proper” frontend framework, your Client-side Javascript will be Spaghetti and Unmaintainable.

This may or may not be true.

Who cares? I love Spaghetti.

I like to argue that some of the most productive days of the web were the PHP and JQuery spaghetti days. A lot of software was built at that time, including many of the popular internet brands we know today. Most of them were built as so-called spaghetti codes, which helped them ship their products early and survive long enough to refactor and not be spaghetti.

Conclusion

The entire point of this talk is to show you that a lot is possible with browsers in 2024. While we were not looking, browsers have closed the gap and borrowed the best ideas from the single-page application revolution. For example, WebComponents exist thanks to the lessons we learned from single-page applications.

So now, we can build very interactive, even offline web applications using mostly browser tools—HTML, CSS, maybe some Javascript—and still not sacrifice much in terms of user experience.